[CS50] TIL CS50X Week 2 - Array part 1

Week 2 - Array part 1

This course is intended for students who have never coded before. The post may be elaborate due to the reason.

🧩 What I Should Learn?

- Compiling

🎯 What I learned today

Week 1 review

What we are going to learn

We previously learned about C, a text-based programming language.

In this lesson, we are going to take a deeper look or lower level at how things work at additional building blocks and primitives that will support our goals of learning more about programming from the bottom up.

Fundamentally, in addition to the programming essentials, this course is about problem-solving. Accordingly, we will also focus further on how to approach computer science problems.

Compiling

Ciphertext

The picture below is what we call a ciphertext, the result of encrypting some piece of information.

The encryption is the act of hiding plain text from prying eyes. It’s what we are using on the web, our phones, and the banks. Anything that tries to keep data secure is using encryption.

There are different levels of encryption, and notice that the one above ciphertext isn’t all that strong. But we will see in this lecture how we decrypt this and reveal what the plaintext corresponds to that ciphertext.

Decrypting is the act of taking an encrypted piece of text and returning it to a human-readable form.

Assembler Output

Recall that in the previous lecture, we learned about a compiler, a specialized computer program that converts source code into machin code that a computer can understand.

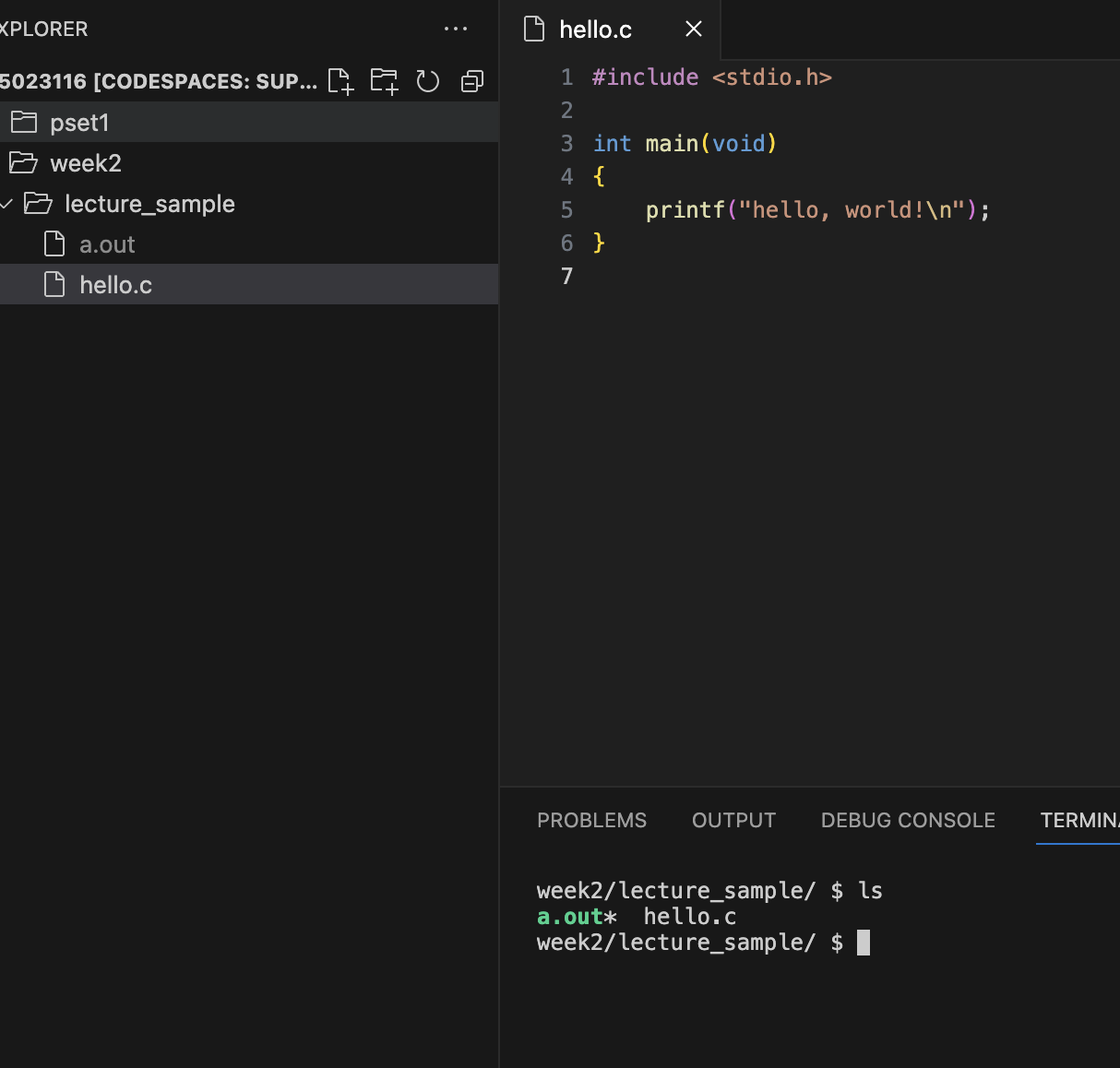

The very first program that we wrote in C was this one:

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void)

{

printf("hello, world!\n");

}

Notice in the previous lecture that we used this function to print something on the screen in an abstract way. However, there was a lot of technical stuff above and below it. For instance, the curly braces, the parentheses, words like void and include, the angled brackets and the like.

Despite the existence of those technical terms, our ultimate goal is to convert that source code in C to machine code, the zeros and ones in binary that the computer understood.

To do that, we ran the following keywords or compiled the code, if you will.

make hello

./hello

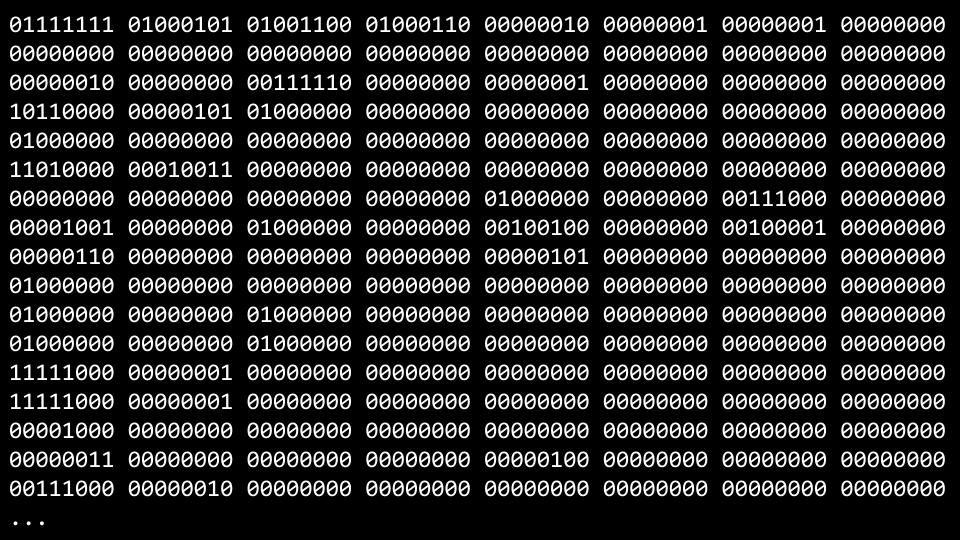

A compiler will take the hello world code above and turn it into the following machine code:

It turns out that the make is not a compiler, as alluded to in the previous lecture. It’s a program that makes our program, but it itself just automates the process of using an actual compiler.

The one that it actually uses underneath the hood is something called Clang for C language. A Clang is a pretty popular compiler nowadays, and VS Code, the programming environment provided to us, utilizes this compiler.

If we were to type make hello, it would run a command that executes Clang to create an output file we can run as a user.

Suffice it to say we want to use a compiler manually. We have to understand the behavior under the make command.

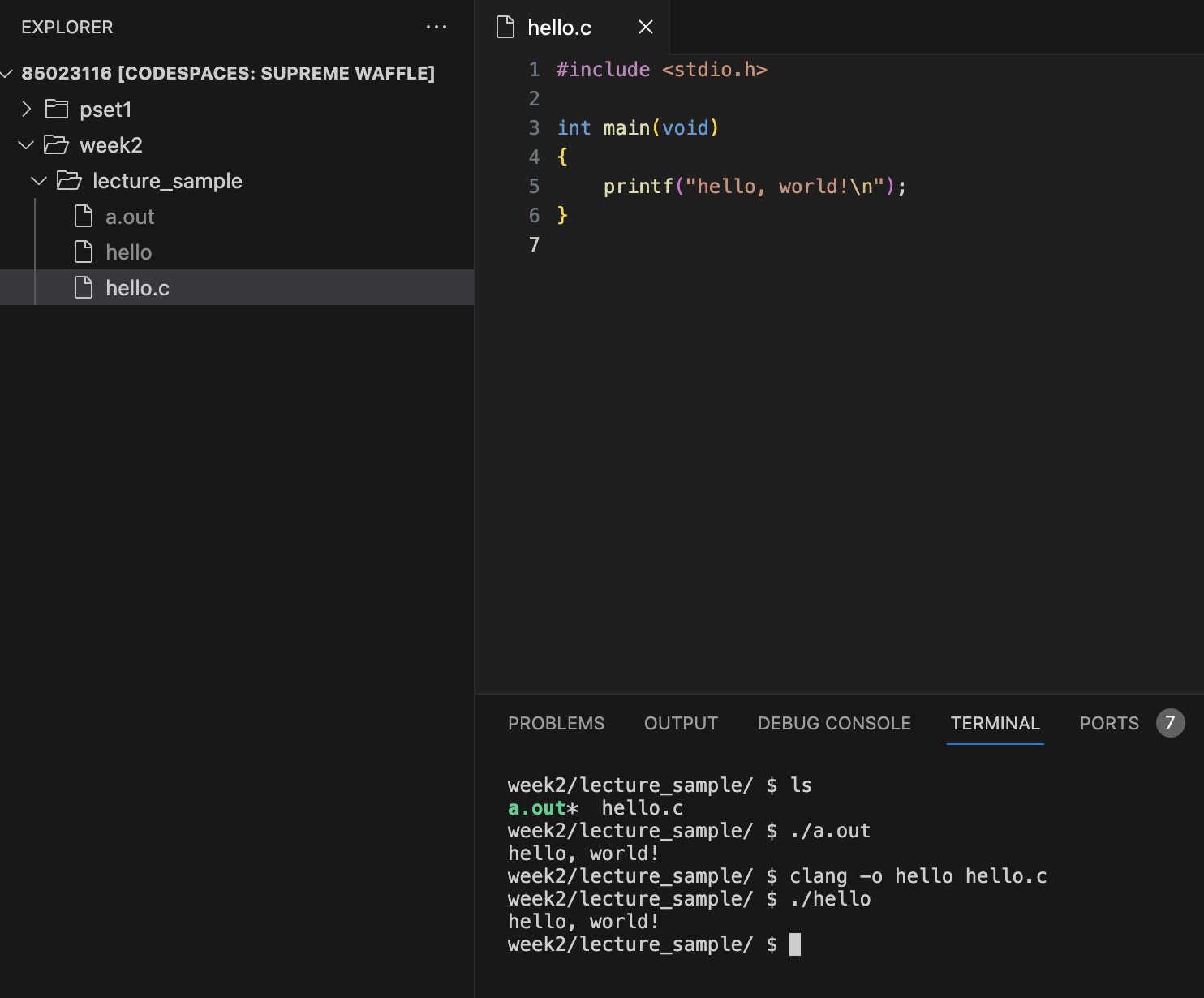

To compile the above hello.c in our terminal with the raw compiler command, we can run clang hello.c.

Notice when we check the file tree, we can see there is a file that’s been created suddenly in the folder weirdly called a.out, and we can see it on the left side’s GUI.

That stands for Assembler Output; long story short, it’s the default name of a program when we run Clang by itself.

That’s an arguably bad name for a program because it doesn’t describe what it does.

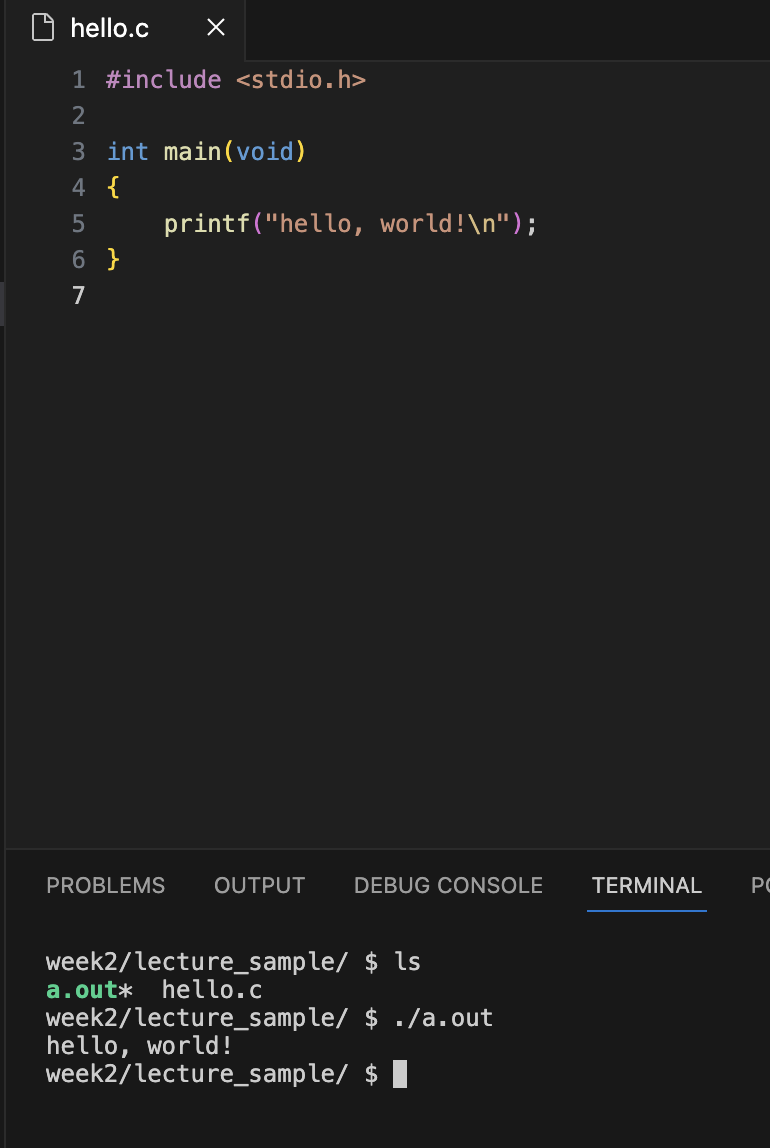

When we run the program with the a.out, it prints out the same result, but it is better to name this program hello as we normally create with the make command.

We could use Linux’s mv command to rename the a.out to become hello, but that too seems tedious. But this is perhaps not the best design because now we have three steps: write the code, compile the code and then rename the code.

To solve this problem, we can use certain commands like clang support, which we call command line arguments.

Command Line Arguments

A command line argument is an additional word or key phrase that we type after a command at our prompt in the terminal window that just modifies the behavior of that command.

clang -o hello hello.c

./hello

With the above command, we can specify the output of this command per this -o. The below picture shows the result of this command.

Notice that the command achieves the same exact effect as make, but we didn’t have to put -o or use clang.

The -o stands for output, so -o means change clang’s output to a file called hello instead of the default file name, a.out. To be simple, we can customize the output of Clang and call it something we want.

In fact, this is also the abstracted version of command in some sense. That’s why we distill this process, ultimately just running the make command. VS Code has been pre-programmed such that make will run numerous command line arguments along with clang for our convenience as a user.

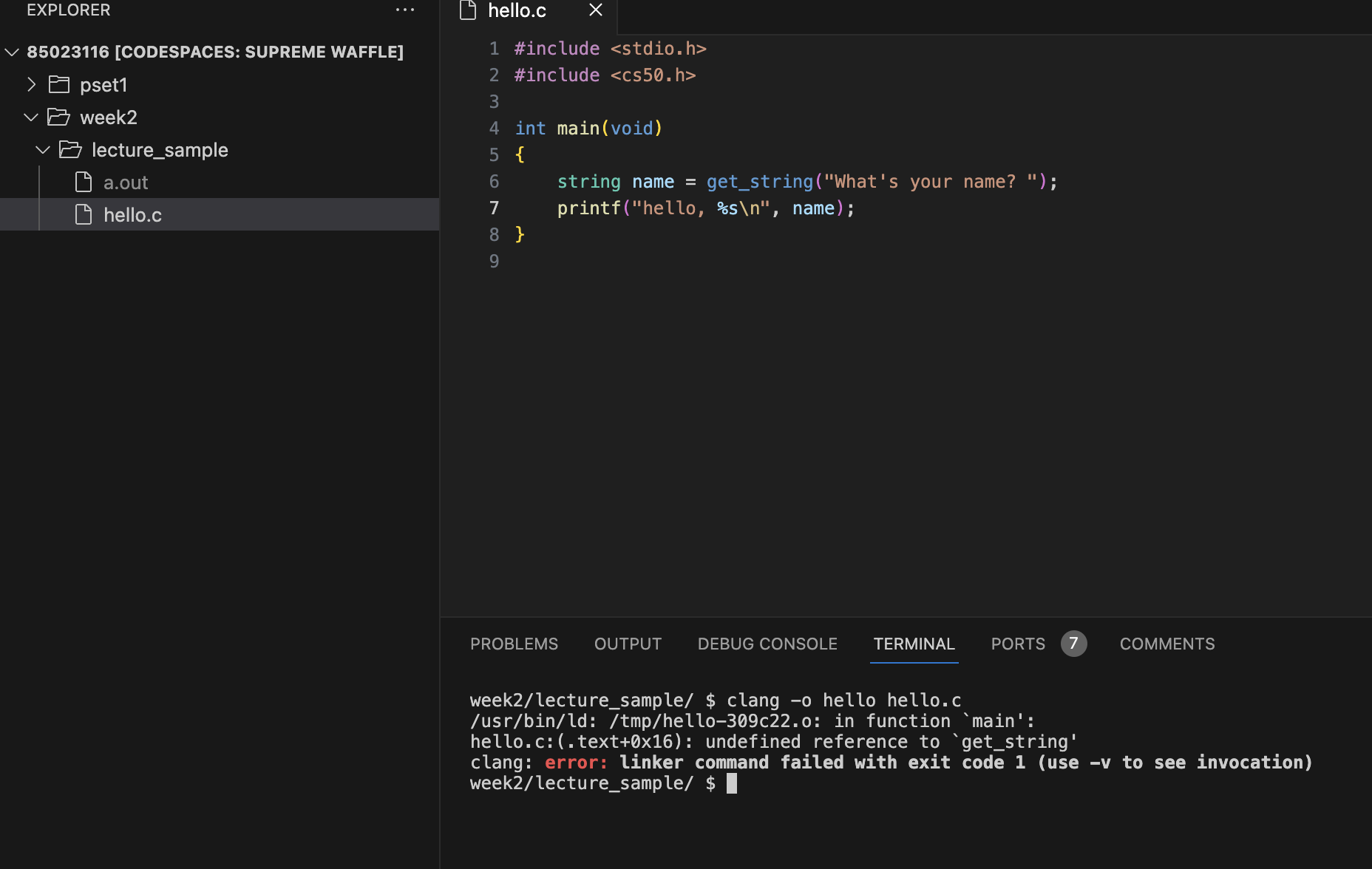

To take a closer look at what is happening underneath the hood, we will change this code to a slightly more complicated version.

After modifying it, we can attempt to enter the same clang command. We will meet the error that indicates that clang doesn’t know where to find the cs50 library.

The error message has a lot of jargon, but one obvious hint is that the get_string reference is undefined. We included the cs50.h file in the header file, which should teach the compiler that functions exist.

In fact, it does teach clang that the get_string function exists. However, it is not sufficient information for clang to find on the computer’s hard drive the zeros and ones that actually implement get_string itself.

In a nutshell, the header cs50 file is a teaser to Clang that you’re about to see and use this function somewhere. But if we actually want to use the zeros and ones that cs50 wrote and bake those into our program, we have to run a slightly different command.

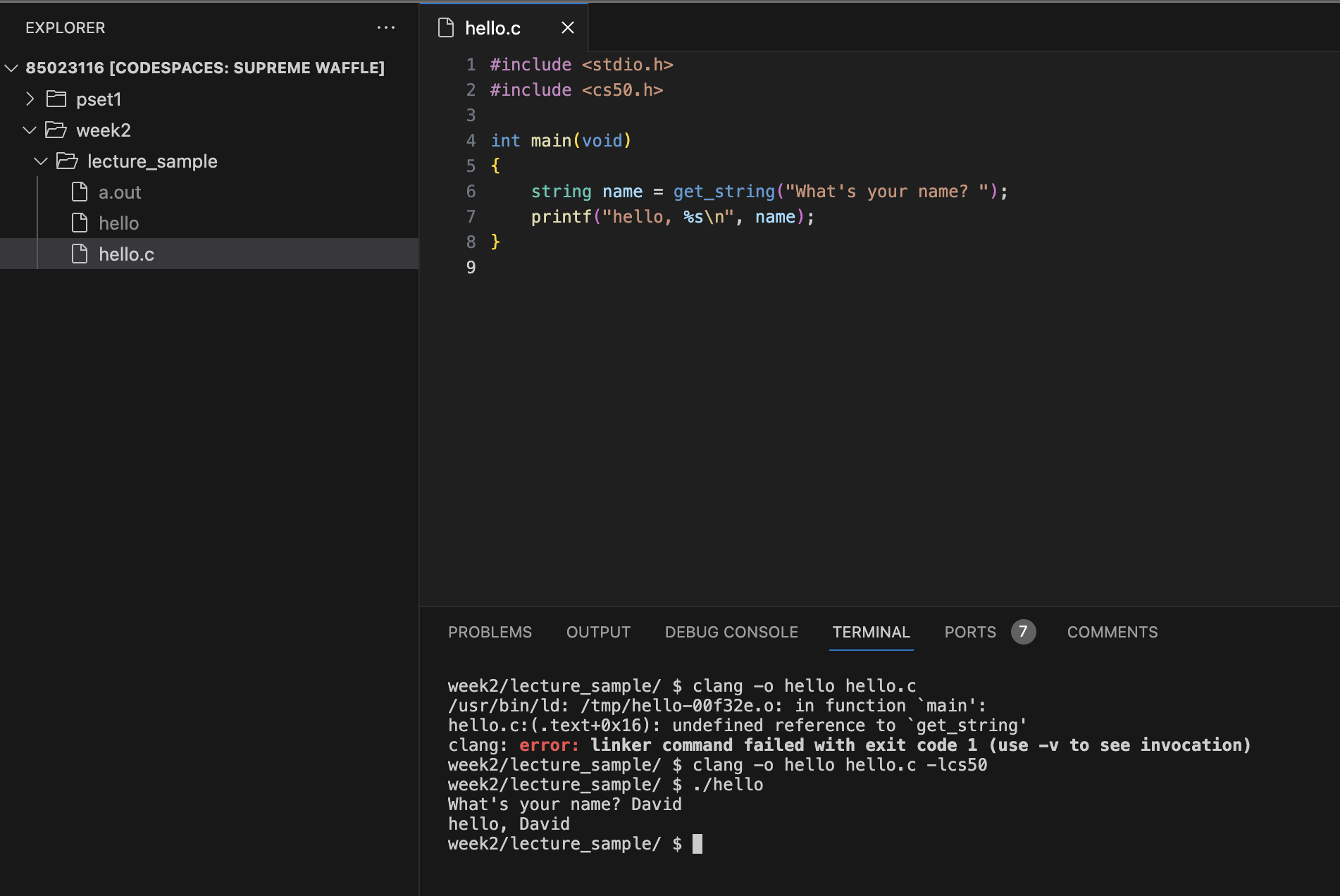

Attempting again to compile this code, run the following command in the terminal window:

clang -o hello hello.c -lcs50

The command above will enable the compiler to access the cs50.h library. That’s the second step that the compiler requires in order to know how to execute rather than compile our code and CS50’s code.

Not only the cs50.h library but also any third-party library in C that doesn’t come with the language, we should attach -l to use their library.

Now, we have seen the process and noticed this is where we are getting in the weeds. That’s just adding a nuisance to the process of compiling and running our code.

Hence, the reality is that even though the above process is what’s happening underneath the hood, we are going to continue to use the command make because it automates the whole process.

Major steps of compiling

When we compile our code, a whole bunch of steps happen. That will enable many features, and the companies can write code and convert it to run it on Macs and PCs or mobile devices.

So, it’s not just a matter of converting source code to machine code. There are actually four steps involved in the compiling process.

Preprocessing

The preprocessing is where the header files in our code, designated by a #, are effectively copied and pasted into our file.

Anything with a hash symbol on the top of the file should be preprocessed, which is analyzed initially before anything else happens.

#include <cs50.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void)

{

string name = get_string("What's your name? ");

printf("hello, %s\n", name);

}

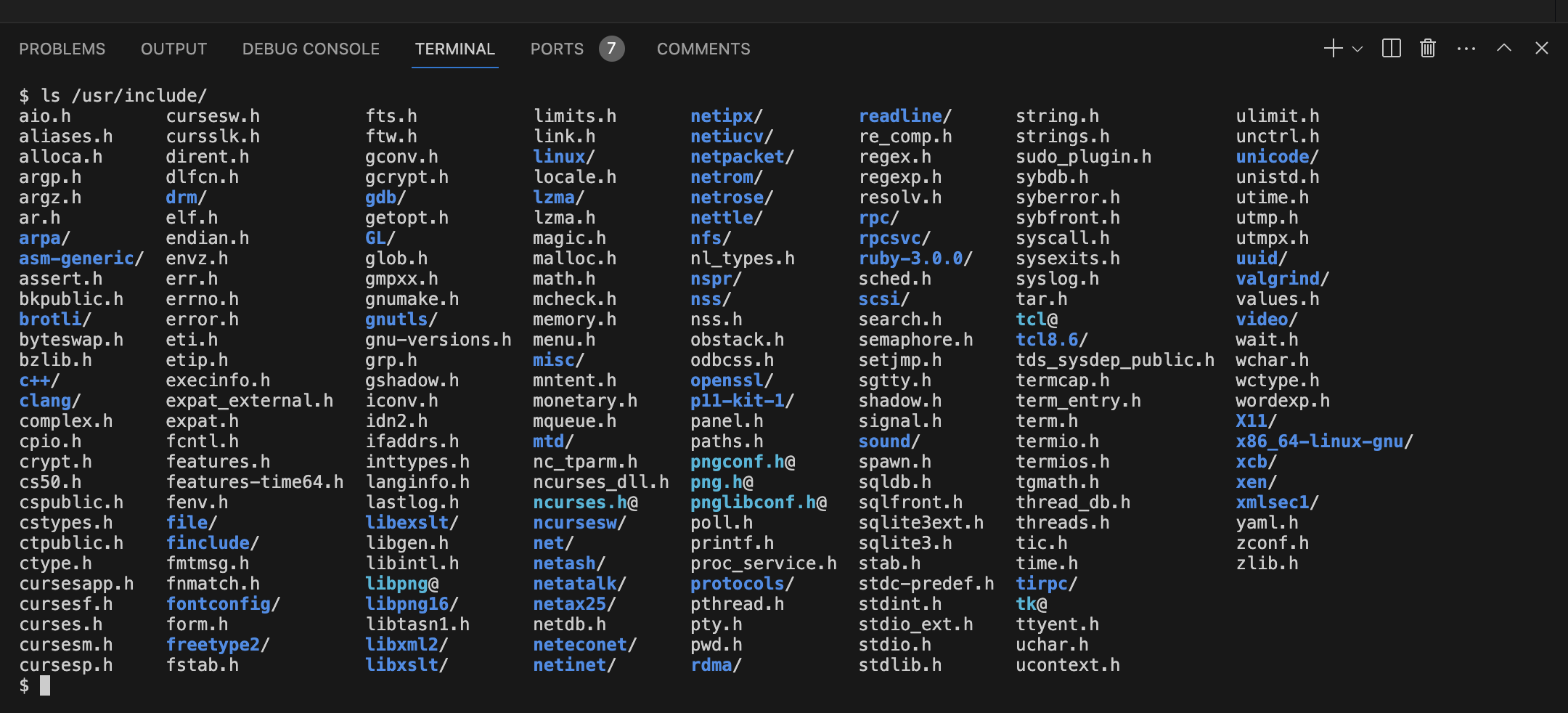

Let’s consider the above two lines up top, what exactly is happening. First of all, where are those files? We never see them; they’ve never been in VS Code, seemingly.

That’s because there’s a folder somewhere on the hard drive we use on our PCs or somewhere in the cloud, as in our case.

Inside of this folder, traditionally called /usr/include. It’s a folder on the server that contains cs50.h, stdio.h and many other things.

If we type ls /usr/include in the terminal, we can check all files in this folder.

As we learned in the preprocessor directive part, we can think of those #include lines as temporary placeholders for what will become a global find and replace.

That is the first thing the clang will preprocess this file, where the clang will look for any lines starting with #include.

If the clang sees that, it will essentially go into that file and copy and paste the contents from that file to our file. We don’t see it visually on the screen, but it’s happening behind the scenes.

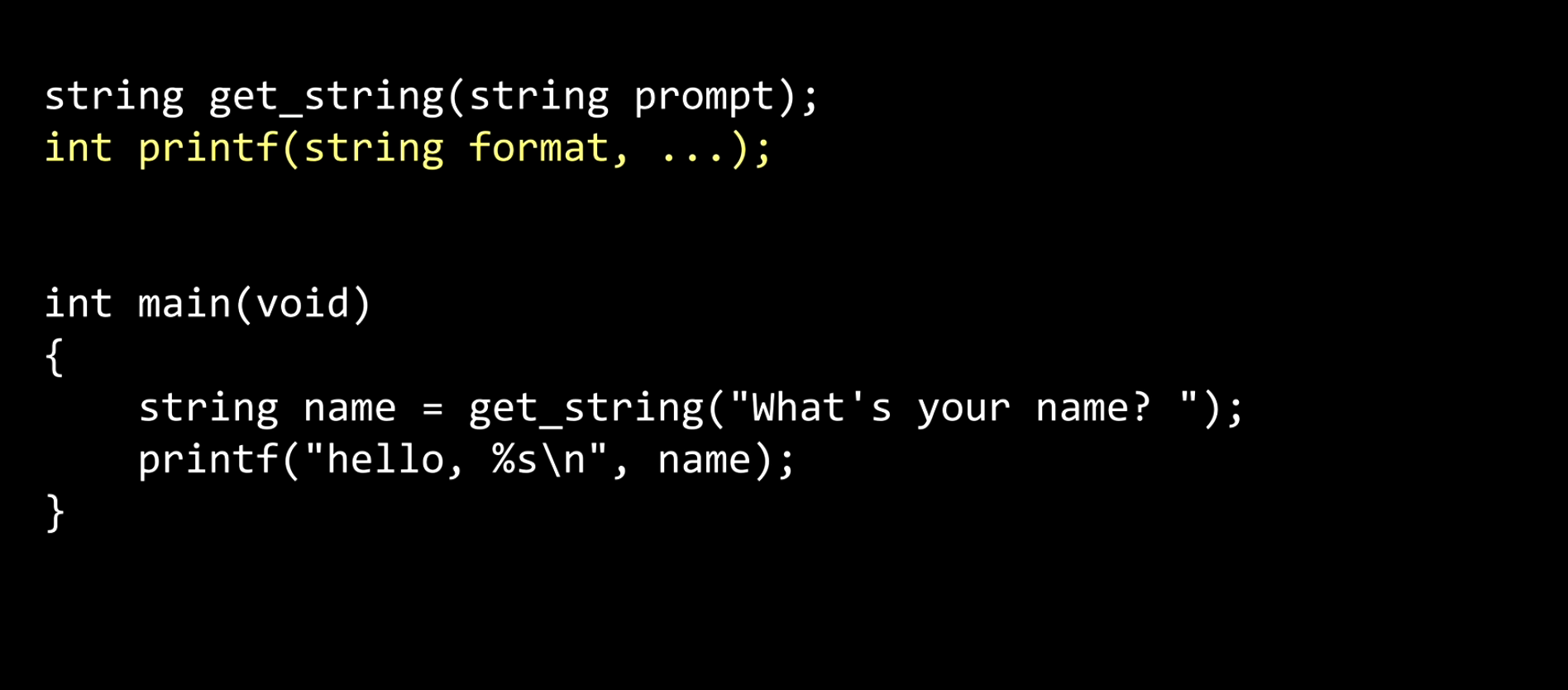

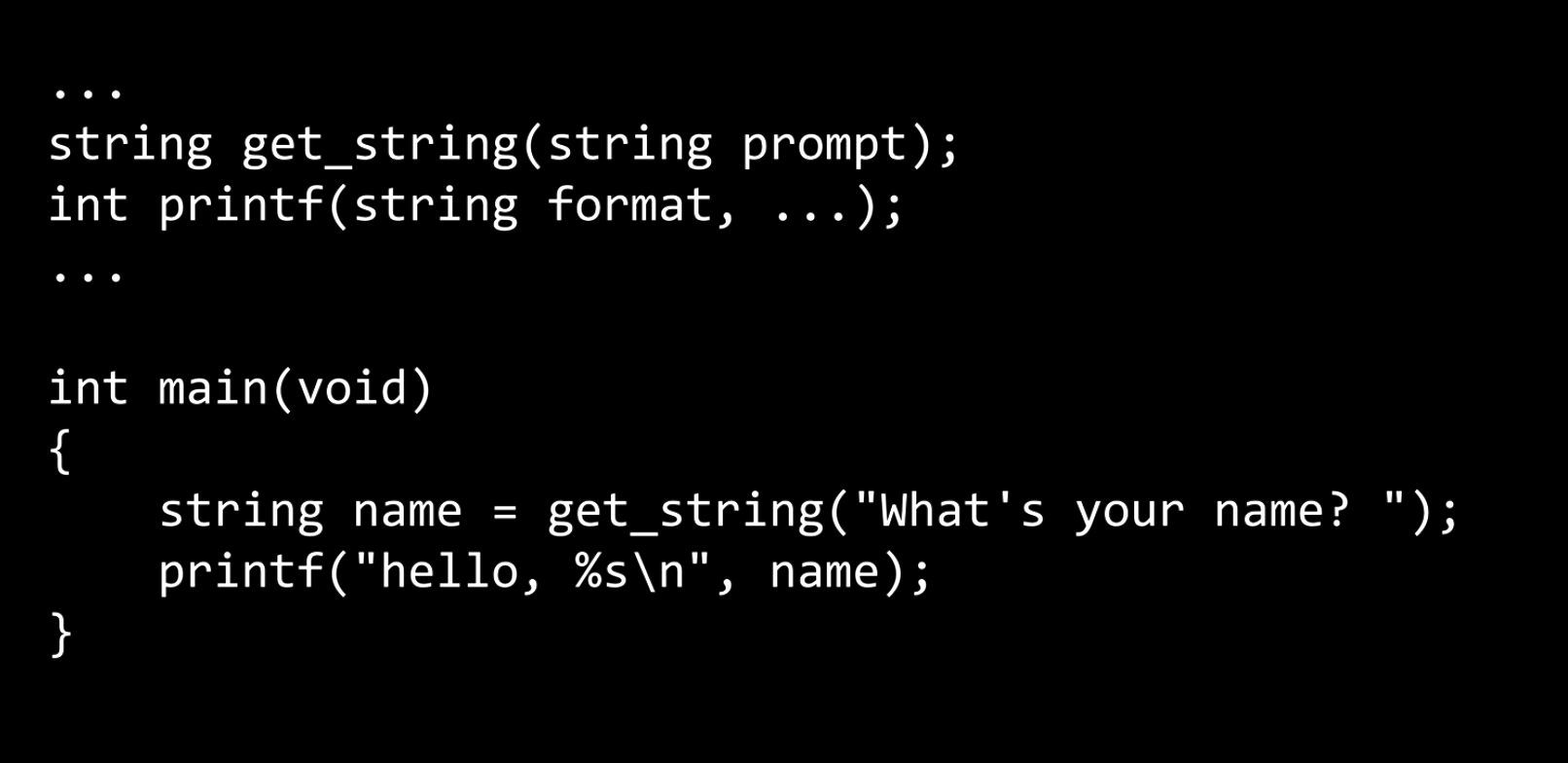

For instance, the first #include <cs50.h> will transfer to string get_string(string prompt), which is the declaration of get_string somewhere in cs50.h.

In detail, the function’s name is get_string, and its arguments are inside the parentheses. In this case, there’s one argument to get_string, which is prompt, and the prompt is a string. The prompt is what the user sees when we use get_string.

Meanwhile, the get_string has a return value as it is a function. The return value is a string.

In other words, we can call this a function prototype, the same as the function type we previously copied and pasted in the last lecture. It was like the teaser for clang or make as to what would exist later.

The second #include <stdio.h> will converted to the printf’s prototype or declaration as the above picture.

It takes a string we want to format, and ... means some variables. Notice that printf returns an integer; we will learn more about that later.

Long story short, think of the #include lines as it combines all of the function declarations in some separate file like cs50.h. As a result, we don’t have to type them every time we use the library or copy and paste those lines every time.

That is what clang is doing for us in its first step of preprocessing.

Compiling

The step two of compiling is, confusingly, called compiling.

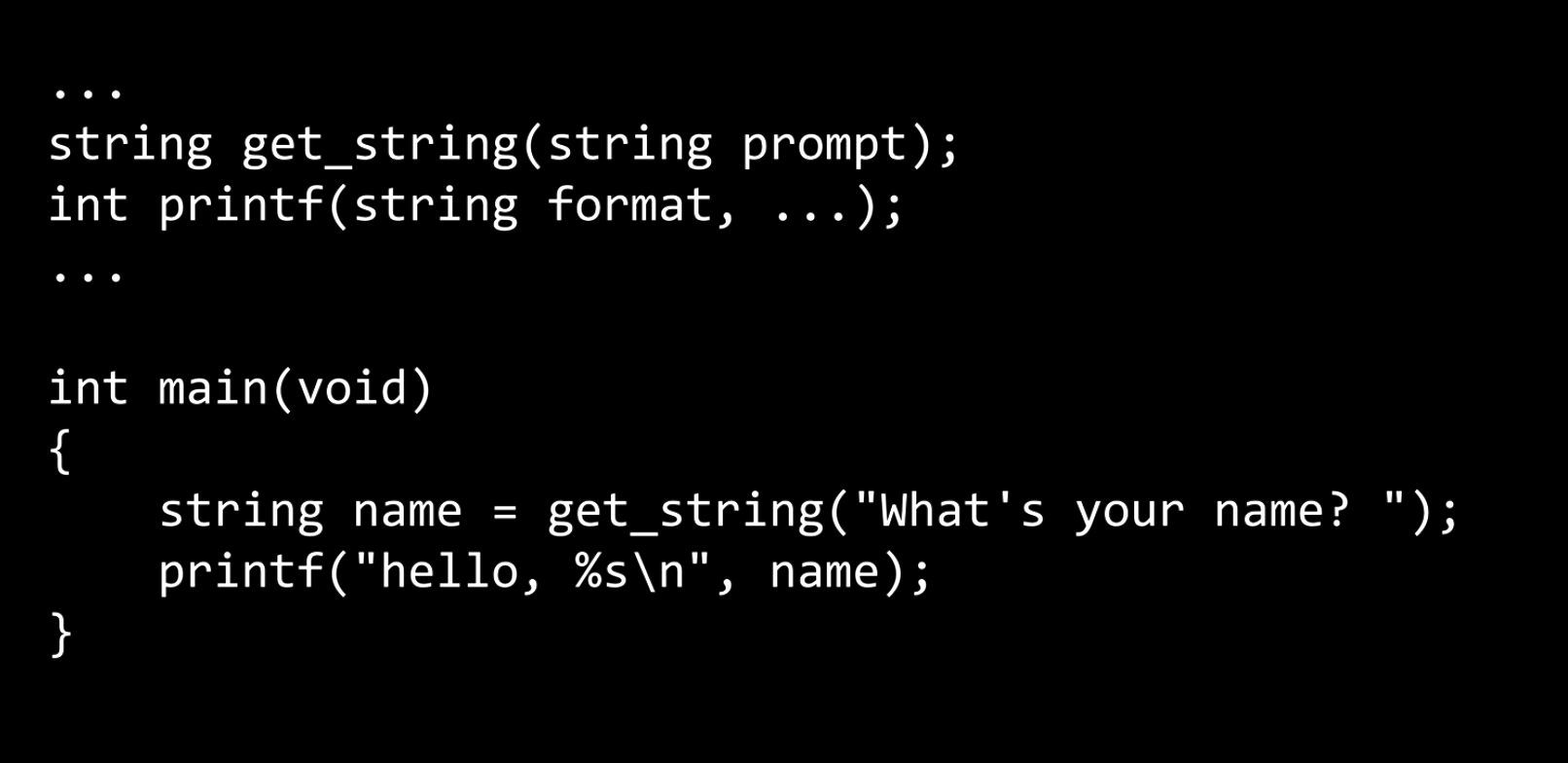

Once the program has been preprocessed by the compiler, it will look like this:

The first and fourth lines ... imply that there is more stuff above and below it, but it is not interesting or related to our code right now.

Now we just have C codes, no more preprocessor directives. At this point, all of the hash symbols and those lines of code have been preprocessed and converted to something else.

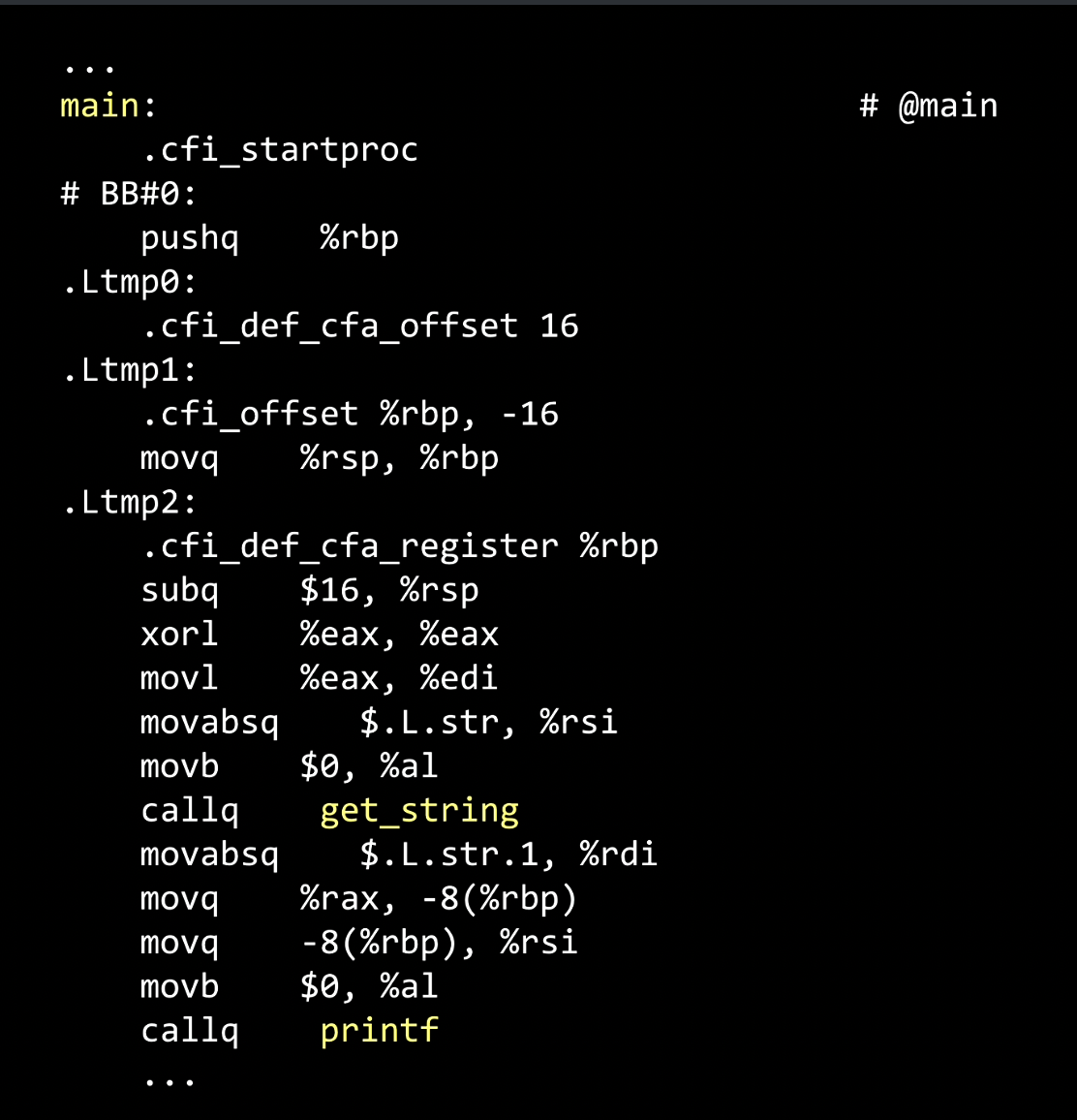

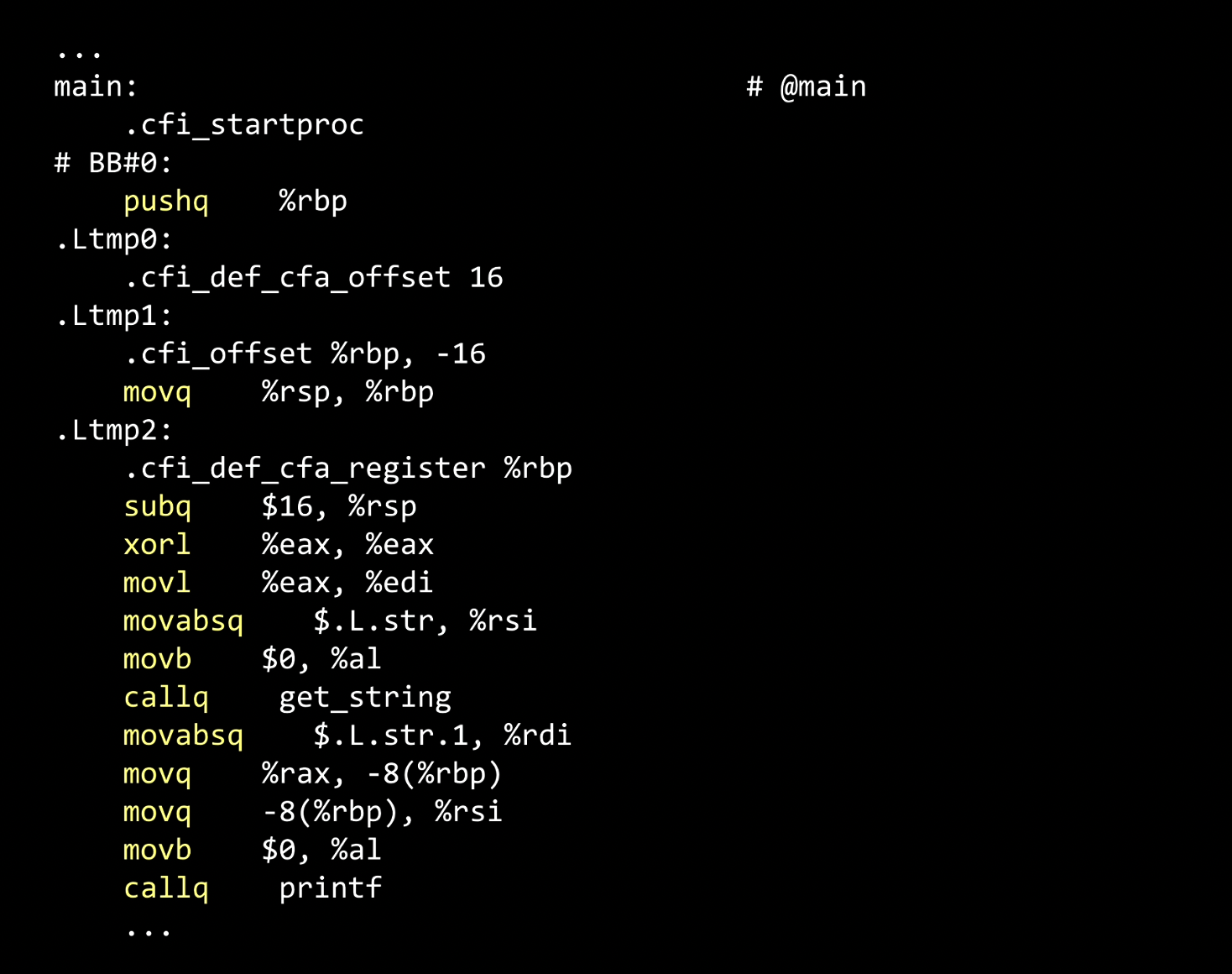

What happens to this code is when clang or any compiler literally compiles code, it converts the code above in C to the assembly code.

The above is not a language many people program in, but at least a few people out there need to know this language because it is closer to what computers understand.

The Intel or AMD CPUs, the brains of today’s computers and phones, understand stuff that looks above and less like C.

It’s completely esoteric, but let’s figure out a few words that are familiar to us. There is mention of main at the top, there in yellow, get_string toward the bottom, and printf down below.

In a nutshell, this is just another programming language called assembly language, which humans wrote this code decades ago. And some people still write this code, especially since we can write very efficient code, although it’s a lot more arcane.

The highlighted in yellow above are called instructions, which a computer’s brain or CPU understands, pushing values around, moving them, subtracting values, calling functions, and moving.

So, the low-level operations that computers understand tend to be arithmetic operations, moving things in and out of memory.

It’s a lot more tedious for folks like us to write code in this language. That is why we tend to write the code like this:

Assembling

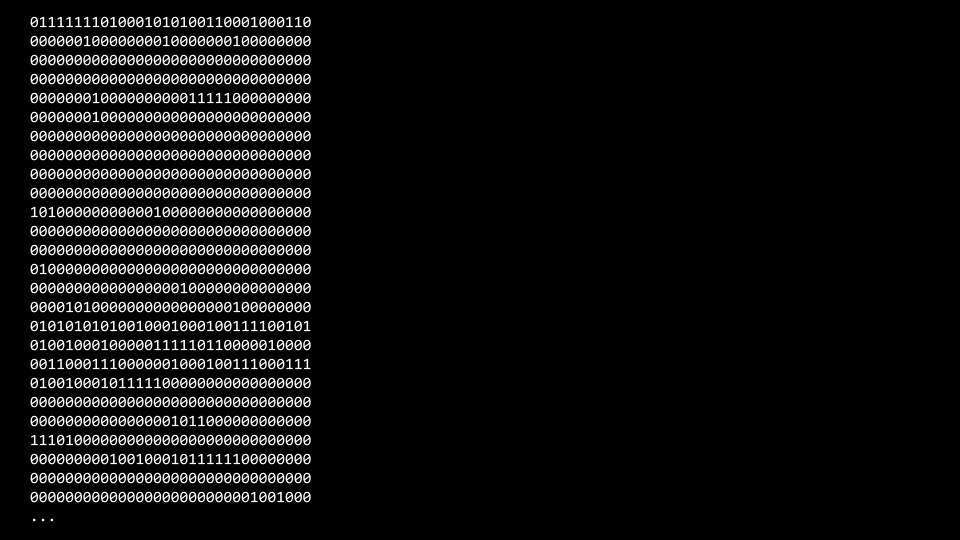

However, as we see the above assembly language, it’s still not zeros and ones. We have two steps to go, and when a compiler proceeds to step three, this is where things get converted to machine code.

When a compiler assembles our code for us, it converts the assembly language above to actual zeros and ones - the machine code that our phone and computer understand.

It’s worth noting that these are not necessarily all of the zeros and ones of our program. They are the zeros and ones that correspond to our hello program or printf and get_string and the like.

But notice that we need one final step, which means they are indeed our program in zeros and ones, but it’s only the program hello’s lines of code.

We might think, what about the cs50 library’s lines of code that we wrote to implement get_string or the printf.

Those are somewhere in the hard drive, like on our Mac or PC or somewhere in the cloud. But we need to combine all of those zeros and ones and link our code with cs50’s code and standard i/o’s code altogether.

Linking

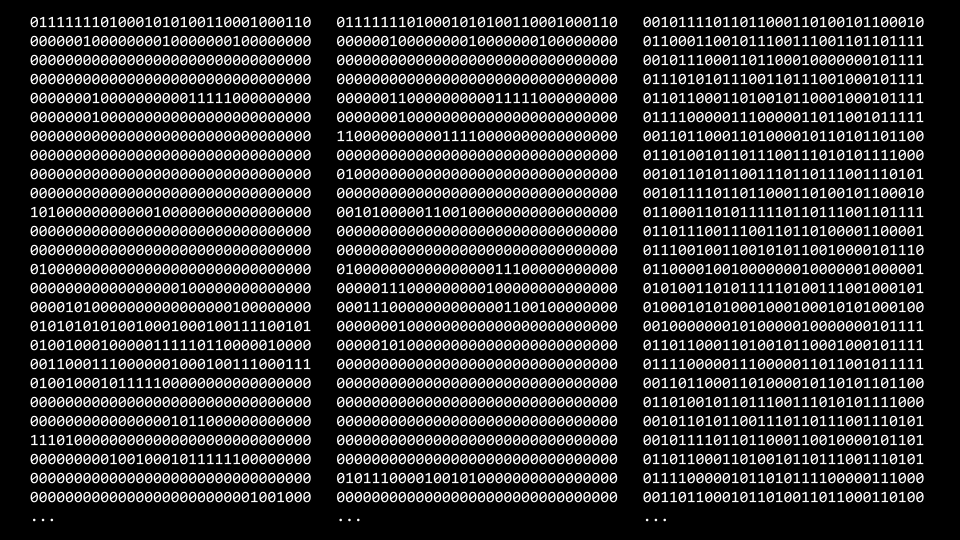

Suffice it to say we have hello.c that we wrote, and there’s somewhere on the computer a cs50.c file that Harvard wrote. Also, let’s assume that somewhere on the computer, there’s another file called stdio.c.

This last step, called linking, takes our zeros and ones from the code that we just wrote above. It then grabs the zeros and ones that cs50 wrote and the zeros and ones that the authors of C wrote in order to implement the stdio.h library.

And links them together will look like this:

The above is the same blob of zeros and ones that we saw in the previous lecture. It’s just now the result of all four steps above. Previously, we’ve taken four processes away and called this whole process as compiling.

Now that we know those steps exist, smart people solve that problem for us. Hence, we can kind of operate at a high level of abstraction and just assume that compiling converts source code to machine code.

Decompiling

Besides compiling, technically speaking, there is decompiling. We will not do this in the course, but it’s worth considering for a moment.

If we look at the word itself, it just means reversing the process - converting it from machine code back to source code.

That might sound cool if there is a program like Microsoft Word, and we can convert it and see the actual source code.

It turns out that it’s not quite as simple as that in the real world. Even though we could take a program like hello that we wrote or VS Code that we use, and convert it from zeros and ones back to some form of source code - be it in C, Java, JavaScript or something else, whatever it was originally written in.

The odds are the converted source code will be an utter mess to look at because the variable names or function names are not typically retained in the zeros and ones.

The logic will retained in the source code, but the computer doesn’t care what pretty variable names the author chose or how we nicely named the functions.

It just needs to know them as zeros and ones. Moreover, we learned three different types of loops, and they are interchangeable.

They look different, and we have to write different code to work with each loop. But they achieve exactly the same functionality.

When we compile a for-loop or while-loop, if they logically do the same thing, they might end up looking identical to zeros and ones.

Therefore, it’s not necessarily predictable that we will get back the original code because the zeros and ones don’t know whether it was which kind of loop and show you one or the other.

Although decompiling is a possible method of reverse engineering a product, if one is skilled enough to read through the intricate code generated by decompiling, one likely possesses the talent to write the same program from scratch.

In general, once code is compiled, it’s pretty challenging, time-consuming, and costly to reverse engineer it. If we think of our phone in the pocket, nothing stops us from opening it up and recreating what’s there.

But that’s a huge amount of effort, and at that point, maybe we should just invent the phone instead of trying to reverse-engineer it.

📌 Takeaway

- Encryption is the act of hiding plain text from prying eyes, and the ciphertext is the result of encrypting some piece of information.

- Decrypting is taking an encrypted text and returning it to a human-readable form.

- The command line argument

makewas the abstraction of compiling, and there is a lot of technical stuff surrounding it. - A

Clangfor C language is a popular compiler nowadays, and VS Code utilizes this compiler. - Run

clang hello.cto compilehello.cin the terminal with the raw compiler command. - The file

a.outstands for assembly output, which is the default name of a program when usingclang. - A command line argument is an additional word or key phrase after the command at the terminal prompt, modifying that command’s behavior.

- The command line argument

-ostands for output, which specifies the command’s output. - The command line argument

-lenables the compiler to access the library that is attached to it. - There are four steps involved in the compiling process.

- The preprocessing is where the header files in the code are effectively copied and pasted and designated by a

#. - The

#includelines combine all the function declarations in separate files and abstract the procedure of typing or copying and pasting the same lines. - Once the compiler preprocesses the program, it converts the code in

Cto the assembly code. - The assembly language is not widely used due to its esoteric nature, but it remains relevant in CPUs and other fields where efficiency is essential.

- The third step is assembling, where the assembly language is not zeros and ones, and the assembly language needs to be converted to binary.

- The last step is linking, in which the compiler brings all the zeros and ones from the libraries and links them to the program that currently uses those libraries.

- Decompiling is the reverse of the compiling process, which means converting machine code(zeros and ones) to source code(

in C). - The decompiling process is extremely complex, and even if we successfully convert some programs, the converted source code will be an utter mess.

- Only the program’s logic is retained during decompiling, not the original variable and function names.

💻 Solution

- None

Continue to part two

🔖 Review

- The command line argument

makejust automates the process of using an actual compiler. - If we type

make hello, it runs a command that executesclangto create an output file we can run as a user. - When we run the raw compiler command without any command line argument, it creates a file called

a.out. - We can customize the output of

clangwith the command line argument-o. - Although it may appear that the required libraries are missing, there is a folder named

usr/includelocated in the hard drive or cloud that contains all the necessary libraries. - We learned about the four steps of the compiling process, but we will keep on a high level of abstraction and assume that the compiler converts source code to machine code.

Comments